As pollution and climate change become growing problems, breaking society’s addiction to fossil fuels is a daunting task. What are the main obstacles holding European biotechs back from building a more sustainable economy and how can we resolve them?

Modern society’s dependence on fossil fuels is unsustainable. Although the Covid-19 pandemic caused a 7% drop in carbon dioxide emissions in 2020 compared to 2019, atmospheric greenhouse gases continue to increase. Additionally, products derived from fossil fuels, such as plastics, are highly polluting and will become more scarce in the long run.

Policymakers in the EU have taken this problem to heart and have pushed through the European Green Deal, which aims to make the EU climate neutral by 2050.

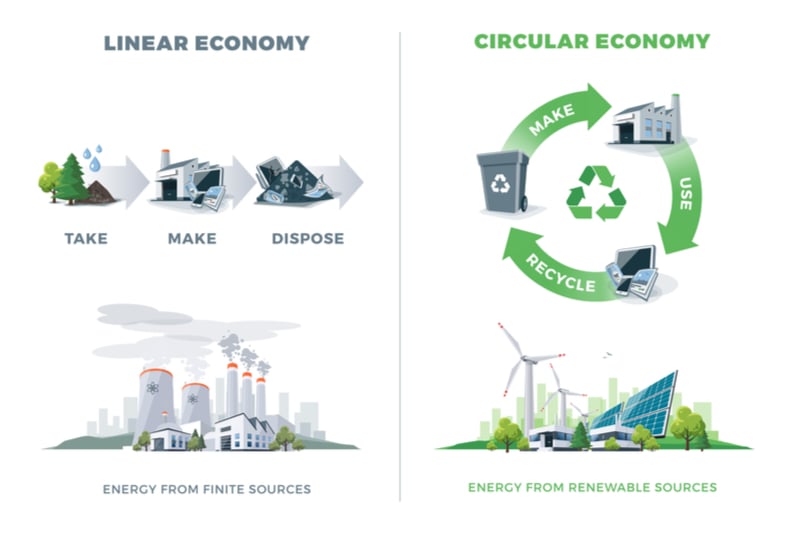

A promising way to meet this target is to replace fossil fuels with bio-based sources of chemicals, food additives, textiles, and even metals. Bio-based sources can include plant crops, waste biomass, and microorganisms like algae and bacteria. Having an economy tied to these sources — a bioeconomy — could mean that we produce less waste and establish a circular economy.

“The circular economy is, in my view, imminent,” said Ullrich Stein, Project Manager at Berlin Partner, a company that helps technology companies find funding. “You have to have it because we don’t have infinite resources. The population is still growing. We need to come up with a ‘zero waste theory’ and therefore a circular economy is what we need.”

Although support is increasing, bio-based industries are still the underdog in Europe. What obstacles are slowing the establishment of European bio-based companies?

The tricky transition to industry

A bio-based economy is driven by innovations, but innovations have to leave the lab and enter the market to make a difference. While Europe has a very strong academic presence in bio-based technology, this isn’t easily transferred to the industry.

“The research is very well established. The industry is waiting for it but they only see a proof of concept and not a demonstration plant, for example,” Stein explained.

According to Stein, academic institutions rarely have the resources to set up demonstration plants with thousands of liters of capacity, so the industry often isn’t interested. “It becomes a ‘valley of death,’” he added.

Thomas Leya, who studies Arctic cold-loving algae at the Fraunhofer Institute for Cell Therapy and Immunology in Leipzig, Germany, is well aware of this challenge. His team sees Arctic algae as useful sources of enzymes that work at cold temperatures, such as those required in the food industry.

In spite of the wide potential of algae as a sustainable source of products like food additives and cosmetics, markets are generally conservative, with cosmetics being the easiest sector to break into.

“[The cosmetics industry] is more accessible for innovative approaches as this market is very trend-driven and is continuously looking for new ingredients,” Leya explained. “Of course, it also is a high-price market … It is easier to market small amounts of costly fine chemicals in the cosmetics sector than bulk chemicals at low prices in other sectors.”

Some public initiatives are already underway to push bio-based technology from academia into the industry, such as a funding scheme launched by the German government in late 2020. However, European policymakers can still do more.

“Increased public funding mechanisms and support with public-private partnerships for the bioeconomy will help to increase bio-innovation and its competitiveness,” said Klaus Pellengahr, General Manager at the Danish enzyme producer Novozymes.

Lack of private investment

The EU provides lots of funding for bio-based technology in the early stages, but European companies have trouble attracting private investors to commercialize the technology.

One reason for this lack of interest from private investors is that the regulatory system is hard to navigate across different EU member states. This means that bio-based companies have an uphill struggle commercializing their technology.

“I find that some regulations, though valuable and sensible for protecting the consumer … need to be reformed so that they are easier to use,” Leya commented. “Feed additives from algae could improve meat and fish quality and survival of fish larvae in hatcheries, but cannot enter the market unless this specific algal species is listed in the novel food catalog. But getting it listed is extremely expensive and takes some years.”

And even if a company does attract private investment, VC firms have short-term goals, which can be problematic for establishing bio-based companies. “VCs are another problem because you have to have an exit strategy in your business. You grow it to sell it, which is not sustainable,” Stein explained.

These issues could be addressed if the government reforms the regulatory system and increases funding programs for the nascent bio-based industry. The European Circular Bioeconomy Fund (ECBF), which was launched last year as part of the European Green Deal, is a step in the right direction.

“I’d love to see a lot more investing by not only the industry, because the industry always wants to make money, but more of a top-down approach by the government,” Stein commented.

Economic short-sightedness

While bio-based industries may provide a long-term value for society, they are usually more expensive than fossil fuel sources in the short term. This means client companies wanting to maximize profits for their shareholders are unlikely to pay for bio-based goods.

“It still is less expensive to use traditional sources as these processes are established and have been used for a long time,” Leya explained. “As long as the traditional resources can still be bought at lower prices than products from alternative bio-based resources, the traditional, chemical, ones will be used.”

Another factor at play is that fossil fuel products are often priced artificially cheaply. For example, members of the European Union granted a huge €50B in subsidies to fossil fuel companies in 2018, and it’s likely these subsidies have increased during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In addition, many companies have been able to pump greenhouse gases into the environment without paying any tax on emissions. While the EU runs a scheme to incentivize reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, progress has been slow.

“If we incorporated a carbon dioxide tax in Europe or worldwide, for example, in an instant many products would double or triple in price. And then a bio-based economy would become much more efficient,” Stein said.

Making the bioeconomy more appealing for the industry, therefore, requires a more level playing field in terms of subsidies, with prices that better represent the environmental cost of the materials. Measures to better integrate bio-based methods into the economy could also bring down costs.

Low public awareness

Another obstacle to bio-based companies is limited public communication about the bio-based industry, particularly during a global pandemic. Well-known figures such as the UK broadcaster David Attenborough have greatly improved public awareness of the need for change, but there is a lot more to teach about the bio-based industry.

“Of course, there is a will of the consumer to use ‘green, sound, alternative’ products, but often they are not willing to pay the price or do not really understand which product really is environmentally green,” Leya said. “A product is not necessarily green just because that word is printed on the label.”

Another factor is public distrust of organisms modified by gene-editing tools, such as CRISPR/Cas9, whose many potential applications include improving the production of sustainable bio-based products like biofuels.

At present, EU regulators reflect this distrust by strictly regulating the commercialization of gene-edited organisms, despite the fact that gene editing is seen as more precise than approved methods of modifying DNA such as mutagenesis and selective breeding.

“If you look at normal genetic modification such as breeding, it’s like firing a shotgun at your genetic material and seeing what comes out,” Stein explained. “If you look at CRISPR/Cas9, you take one gene and replace it — it’s like shooting like a sharpshooter. People don’t tend to know how it works and therefore a lot of education is needed.”

Europe’s long road to sustainability

European biotech companies are definitely making leaps and bounds in the development of a circular economy. One case is the French biotech Carbios, which is developing ways to turn old clothes into recycled plastic bottles. In December, another French biotech called Afyren started construction of a factory turning plant waste into industrial chemicals. Meanwhile, the Finnish company Solar Foods was one of many meat alternative biotechs enjoying an investment surge last year.

Even with advances in biotechnology, the circular economy is still a long way off from becoming a reality. A lot of the challenges boil down to the idea that the cost of doing bio-based business is higher than business based on fossil fuels. Policymakers, therefore, will need to continue investing big public grants into kickstarting the circular economy.

An equally big responsibility falls on the consumers to demand more bio-based sources from companies and governments. “It is the market that will regulate the entry of algal biotechnology onto the everyday market,” Leya said. “That’s the good and the bad side of a free market.”

Achieving sustainability will also involve improving how efficient we are with resources in the first place. “I doubt that we can convert our complete industry into a green one unless we start using fewer resources much more efficiently,” Leya added.

In terms of policy, the Green Deal and ECBF mark a sea change in government and investor attitudes towards the bioeconomy.

“Society and more and more politicians are recognizing step by step that the transformation process is not just an option; it’s an urgent must. The Covid-19 crisis has fueled the change in mindset,” said Michael Brandkamp, General Partner of the ECBF. “The topic of sustainable investments is becoming more important. This will have a very positive effect on the financing of bioeconomy companies.”

However, the profound impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the European economy leaves big question marks over the coming years. Additionally, the long-term effects of Brexit on synthetic biology research is still to be seen.

Nevertheless, Stein hopes that bio-based companies will increase their foothold in the market going forward.

“My biggest hope would be that elements of a circular economy get incorporated into the real industry,” he concluded. “This means everything that comes with it: resource efficiency, sustainable energy. I’d love to see it. And I’m definitely working on it.”

This is an updated version of an article published on the 25th of June, 2018. As of the update, Ullrich Stein is now Transfer Manager at the Fraunhofer Institute for Applied Polymer Research IAP, but wished to have his comments associated with his previous position.

Cover image from Elena Resko. Text images from Shutterstock, Tobias Marschner for Fraunhofer IZI-BB, Felix Jorde